The Church of St Denys, which is almost invisible from the town centre owing to its long and low form, is mainly a product of the Victorian era, with some notable medieval work remaining mostly in the north transept and central tower. The low central tower, not quite 50 feet high, contains one of the county’s heaviest sets of eight bells, with a tenor of 23 and a quarter cwt. For a small market town in a rural corner of Wiltshire, the history of the bells at Warminster is unusually complex. The earliest record of bells at Warminster is in the 1553 inventory where it is recorded that St. Denys had six bells, including a sanctus.

Warminster is an ancient town dating from at least the Saxon period, but the surrounding hillforts provide evidence of continuous human occupation for thousands of years. The origin of the first element of the name Warminster is not clear but the -minster suffix refers to a Saxon teaching church and monastery and is an indication of one of the very first foundation churches dating from the period in the mid seventh century when the leaders of the predominantly pagan English were beginning to invite missionaries to their royal or noble estates to preach and baptise their people. The present parish church of St Denys, located in the northwestern extremity of the town, is commonly referred to today as just ‘the Minster’.

In John Daniell’s History of Warminster (1879), he writes that in 1629, the great bell was “broken by mischance” (p. 159) and sold to Warminster bell founder John Lott at 10d per lb, with the proviso that the replacement bell was no lighter than the original. In 1686, the fourth was recast by John Lott II, John Lott’s son, presumably because it had cracked or broken. Lott took payment from the scrapping of the old bell at a rate of 20s per cwt, making a total of £17 14s 6d according to Daniell. The new bell weighed 17cwt 1qr 18lb. (Walters, Bells of Wiltshire, pp. 226-227). The next fifty years had a frenzy of bell recasting at Warminster, with the tenor in particular recast three times in thirty years: by Richard Lott in 1707 for £46 5s, by William Cockey of Frome in 1734 for £29, and lastly by Abel Rudhall of Gloucester in 1737, for £190 1s 9d. The details of Lott’s tenor bell do not survive, however, we can assume, because Cockey’s bell, which was only £29 and reputed to weigh only 25cwt, that Lott’s bell was larger.

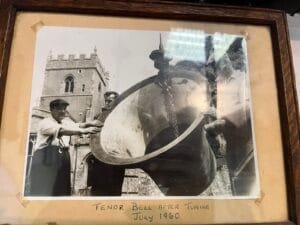

Rudhall’s tenor bell, which still forms the present tenor today, was installed in the tower on 2nd November 1737, weighing 27cwt 2qr 13lb. Canon removal in 1881 and possibly, some retuning in 1960 by Mears, resulted in a weight of 24cwt 3qr 8lb before the 2022 restoration. The bell has decorative arabesque lettering, with a fleur de lys border below. The bell was welded in the recent restoration. Recastings continued into the middle of the 18th century, with the second being recast by Cockey in 1732 for £14 4s 10d, the fourth by Thomas Rudhall in 1765, and the treble by William Bilbie in 1781. Curiously, the inscription for the fourth (the original second) states that it was recast by Cockey in 1739, which, assuming that both dates are correct, would be the second time in the 1730s that one of his bells for Warminster failed in less than ten years, the other being the tenor.

The final recasting, before the 1881 augmentation, was the treble, by James Wells of Aldbourne in 1805. In 1881, all the bells, other than Rudhall’s tenor, were recast by Warner & Sons in Cripplegate. Walters notes in his Church Bells of Wiltshire (1929), that the fifth bell (of the original six) survived until this restoration, and was probably cast in 1410 by Robert Burford of London (p. 227), based on the decoration of similar bells at Gloucester Cathedral (ninth and tenth of the present twelve) and Bristol, St Werburgh (tenor). He doubts, however, that the inscription on the recast bell was replicated accurately.

The present frame dates from a 1914 rehanging by Alfred Bowell of Ipswich, who also provided all the bells with new steel headstocks, which were still on the bells until their recent rehanging. The frame is of a non-standard layout, probably forced by the fact the bells are probably too large for the tower, and the low height of the roof preventing the hanging of the bells on two levels. The frame, constructed from steel, is of low-side design, with multiple cross (‘X’) braces as the trusses. The two largest bells both swing north-south, though roped opposed, as do the third and fourth on the east side of the tower. The other two pairs swing east-west.

The fittings, were, until 2022, comprised massive Bowell steel headstocks, rehung on ball bearings in Mears’ housings by the latter in 1960. The lack of space in the belfry caused particular problems with the clappering in recent years, with several of the flights being cut down on the bigger bells in an attempt to aid in getting the bells ‘up right’. Following their restoration, which was carried out by Matthew Higby & Company of Radstock in 2022, the bells received mostly new fittings. A completely new set of wheels was manufactured by Blyth & Co Ltd of Newark, together with new clappers, headstocks, and ball bearings (in the existing Mears housings) by Higby.

Warminster Bell Foundry

Whilst many of those in the town and indeed those who ring in the surrounding area are aware of the bells of the Minster, there are only comparatively few who know that Warminster had a bell foundry. Located in what is now the Close, the earliest record of a foundry here is in a letter from the churchwardens at Charlton in Somerset, who write to Richard Purdue, normally based nearer Bristol, to request the recasting of one of their bells. However, in the letter, they make clear he appears to be based in Warminster!

This is something of a historical anomaly, as evidence prior to the discovery of this letter generally indicates the Warminster foundry, which operated in the 17th and 18th centuries, was run by John Lott I, then by his sons. We do know, however, that John Lott I was an apprentice of Richard Purdue, and many of Lott’s bells have a similar type of flat capital on the crown of the bell, that can also be found on some of Purdue’s early bells. It is possible that Richard Purdue was the owner of the foundry, and that at some time in the future, John Lott took over the business. We may never know.

Though it did not operate for long compared to other foundries at Gloucester, Salisbury or London, for a small market town, the Lott family managed to produce a surprising number of bells. Dove’s Guide records 53 bells still in existence today that were cast at Warminster, in various churches across the area, dating from between 1624 and 1711, though the foundry was known to be in operation for several more decades. The largest and probably most historically important of these is the 27 cwt tenor at Frome, cast in 1662, followed by the ninth at Edington at just over 15 cwt. Other churches in the area with notable Lott bells are Codford St Peter, Erlestoke, Durrington, Enford, and Sedgehill, which all have two surviving Lott bells in their rings.

There is very little sign of Lott’s foundry now, and we do not know exactly where on the Close it was located. The only clue now is Forge Cottage, located just behind the Close on North Row, though in a row of Georgian cottages, the only more modern building in that area is the Warminster Baptist Church, which sits between the two aforementioned lanes and was built in 1810. Very few of the other buildings have changed, so the evidence of the foundry, if indeed there is any left, is likely to be under the cemetery of the church, which is the only open space along the Close and North Row. The chances of a dig in this area are close to zero, so imagination will have to be used as to what it looked like and where exactly it was located.

Whilst none of Lott’s bells survive at Warminster itself, the metal does, in the present tenor bell. There is something distinctly satisfying from a historical point of view in ringing a bell that was made in the very town you are in. Why not investigate the history of the bells in your tower? You never know what you might find out!

Jack Pease